By Kanya D'Almeida

When Sri Lankan journalist Richard de Zoysa was abducted from his home in Colombo on the night of February 18th, 1990, his family knew there would be dark days ahead. The population was still reeling from one of the bloodiest episodes in the island nation’s history – a government counterinsurgency campaign to crush a Marxist rebellion in southern Sri Lanka, which left between 30,000 and 60,000 people dead at the hands of government death squads.

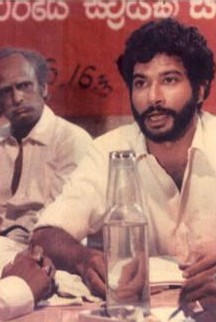

The late Richard de Zoysa, former IPS UN Bureau Chief in Sri Lanka.

The late Richard de Zoysa, former IPS UN Bureau Chief in Sri Lanka.

Even more disturbing than the extrajudicial killings was the wave of enforced disappearances that took place between 1988 and 1990: tens of thousands of Sinhalese men and boys suspected of being members or sympathizers of the People’s Liberation Front, or JVP, went missing, never to return.

At the time of his kidnapping, de Zoysa was a stringer for this publication, filing regular reports on the political violence plaguing the country. He was on the verge of accepting the post of Bureau Chief of the agency’s Lisbon-based European desk when the goons came knocking.

For hours that bled into days, his mother, Manorani Saravanamuttu had no idea what had become of him. High-ranking officials assured her that he was alive, in police custody, but refused to give her exact coordinates when she asked to be allowed to bring him some clothing – he had been wearing only a sarong when he was kidnapped – or a meal.

It later transpired that while she was making frantic phone calls and searching for answers, de Zoysa was already dead, shot in the head at point blank range, and his body dumped in the Indian Ocean, a tactic that had become a common feature of the government’s systematic abductions.

A fisherman happened to recognize his face – de Zoysa was also a well-known television personality at the time – when his body washed up on shore in a coastal town just south of the capital. He alerted the authorities who in turn contacted de Zoysa’s mother.

According to a 1991 Washington Post interview with Saravanamuttu, the discovery of her son’s body was a turning point, for her personally, and for the nation as a whole. When she walked out of the inquest a few days after de Zoysa’s abduction, she found herself surrounded by reporters, to whom she made a statement that resonated with countless families across the island: “I am the luckiest mother in Sri Lanka. I got my son’s body back. There are thousands of mothers who never get their children’s bodies back.”

Mothers of the Disappeared

Saravanamuttu’s statement quickly catalyzed a movement known as the Mother’s Front, which had been a long time coming. Perhaps due to her privileged status as a member of the country’s English-speaking elite, she became a kind of totem pole around which women from the poorer, politically marginalized and largely Sinhala-speaking rural belt could gather, and from which they could draw strength. By 1991, according to the Post, the Mother’s Front counted 25,000 registered members.

The movement did not succeed in bringing justice to many of its victims. To this day, not a single person has been convicted for de Zoysa’s murder. Ministers who opposed Saravanamuttu and others’ attempts to seek answers in the murders or disappearances of their loved ones continue to hold positions of power within the government – Ranil Wickremesinghe, who the Post quoted as brushing de Zoysa’s murder off as “suicide or something else”, now serves as the Prime Minister, the second-highest political office in the country.

Amnesty International estimates that since the 1980s, there have been as many as 100,000 enforced disappearances in Sri Lanka.

The Mother’s Front movement did, however, make a crucial contribution to the country’s political landscape, one which continues to have ramifications today: it tied together forever the plight of Sri Lanka’s disappeared with the fate of its journalists and press freedom – or the lack thereof.

Exactly 20 years after de Zoysa was assassinated, another journalist’s disappearance prompted a woman to step into the global spotlight, much as Saravanamuttu did back in the 90s. This journalist’s name is Prageeth Eknaligoda, and he was last seen on January 24th, 2010. He telephoned his wife, Sandhya around 10 p.m. to inform her that he was on his way home from the offices of Lanka eNews (LEN), where he was a renowned columnist and cartoonist. He never arrived.

From local police stations all the way to the United Nations in Geneva, Sandhya has searched for answers as to his whereabouts. It is only in the last two years that some information regarding his abduction and detention by army intelligence personnel has been revealed.

Both Saravanamuttu and Sandhya Eknaligoda have received international recognition for their tireless campaigning. In 1990 de Zoysa’s mother accepted IPS’ press freedom award at the United Nations on her son’s behalf, and last year Sandhya was honored with a 2017 International Woman of Courage Award. But back in Sri Lanka, she faces a government and a public that is at best indifferent, and at worst openly hostile to her continued efforts to find her husband.

A New Front: Tamil Women in the North

Sandhya has also been one of the few women, and one of the lone voices, connecting the issue of press freedom with the movement of families of the disappeared led by Tamil women in Sri Lanka’s northern province, where the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) waged a 28-year-long guerilla war against the Government of Sri Lanka for an independent homeland for the country’s Tamil minority.

Since January 2017, hundreds of Tamil civilians have observed continuous, 24-hour roadside protests in five key locations throughout the former warzone – Kilinochchi, Mullaithivu, Trincomalee, Vavuniya and Maruthankerny (Jaffna district) – demanding answers about their disappeared loved ones.

Like the Mother’s Front in the 1990s, this movement too has been several years in the making. When the civil war ended in 2009, some 300,000 Tamil civilians were rounded up and detained in open-air camps, while hundreds of others – particularly men who surrendered to the armed forces – were taken into government custody under suspicion of being members or supporters of the LTTE.

But while the camps have closed and a large number of people reunited with their families, an estimated 20,000 people are still unaccounted for, including those who disappeared in the early years of the conflict, as well as others who have been abducted as recently as 2016 and 2017.

In 2016, Parliament passed a bill to establish an Office of Missing Persons (OMP) tasked with investigating what Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera called “one of the largest caseloads of missing persons in the world.”

However, rights groups like Amnesty International raised concerns about the bill, including the government’s failure to consult affected families throughout the process. This past March, the government passed a bill that would, for the first time in the country’s history, criminalize enforced disappearances.

But these cosmetic measures have failed to yield concrete results.

In an interview with IPS, Ruki Fernando, a Colombo-based activist who has been visiting the protests in the northern province, noted that Tamil families’ decision to spend day after day in the burning sun by the side of polluted, dusty highways and roads is indicative of their lack of faith in government mechanisms like the OMP and the judiciary to bring them relief. He also called attention to the dismal levels of support or solidarity they have received from Sri Lanka’s broader civil society, including from English and Sinhala-language media or women’s groups in the capital.

“It’s not fair that these families – particularly elderly Tamil women who are leading the protests – should have to carry this burden alone. They have already suffered heavily during the war – they starved in bunkers, they didn’t have medication for their injuries, they have lost family members. All these factors have made them physically weak and emotionally vulnerable, yet now they are also shouldering the burden of keeping these protests going.”

He recalls meeting women as old as 70, adding that protestors sometimes don’t have food, and must endure the vagaries of the weather in the arid northern province. Some of the younger women are forced to bring their children with them. And most, if not all of these families, face the additional financial hardship of having lost their primary breadwinner, or losing out on livelihoods in order to participate in the protests for long periods.

“In my memory, such a strong movement led by women, occurring simultaneously in five locations across the North and East, or any region, is unprecedented,” Fernando said. “And yet it has not become a priority for the rest of the country.”

He called Sandhya Eknaligoda’s participation in the protests as a Sinhala Buddhist ally an “exception” to the rule of general indifference, which he chalked up to a combination of political and ideological issues.

“Some people believe these protests are too radical, too politicized, that there should be more cooperation with, and less criticism of, the government,” he explained. But as Fernando himself noted in an article for Groundviews, one of Sri Lanka’s leading citizen journalism websites, Tamil families have met repeatedly with elected officials, including President Maithripala Sirisena, to no avail.

No Closure

Fernando is not the only one to draw attention to Tamil families’ disadvantaged position with regard to both deaths and disappearances.

Another person to make this connection was Lal Wickrematunge, the brother of journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge, former editor-in-chief of the Sunday Leader who was murdered in broad daylight in 2010, and whose killers still haven’t been brought to justice.

Lal pointed to the ongoing investigation by the Criminal Investigation Department into military intelligence officers’ involvement in the kidnapping and torture of former deputy editor of The Nation newspaper, Keith Noyahr – and the arrest earlier this month of Major General Amal Karunasekera in connection with multiple attacks on journalists, including Noyahr, and Lasantha Wickrematunge – as a possible avenue of closure for the families.

According to a recent report in the Sunday Observer, “The assault on former Rivira Editor Upali Tennakoon and the abduction of journalist and activist Poddala Jayantha are also linked to the same shadowy military intelligence networks, run at the time by the country’s powerful former Defence Secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa.”

But Lal Wickrematunge told IPS in a phone interview that while his family, along with international rights groups, are “keenly watching the progress of the investigation, which will determine if the government is serious about law and order”, he is concerned about those who may never receive answers – such as the families of two Tamil journalists who were assassinated in 2006.

Suresh Kumar and Ranjith Kumar were both employees of the Jaffna-based Tamil-language daily Uthayan, whose employees and offices have been attacked multiple times, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Other disappeared Tamil journalists whose cases receive scant attention include Subramanium Ramachandran, who was last seen at an army checkpoint in Jaffna in 2007.

For Fernando, the task of keeping the torch lit for Sri Lanka’s dead and disappeared cannot be laid at the feet of their family members alone – it is a responsibility that the entire country must share.

“What we need first and foremost are independent institutions capable of meting out truth and justice and winning the confidence of the families. And secondly, there is a need for stronger support for victims’ families from civil society – activists and professionals like lawyers, journalists and women’s groups.”

“Pushing for answers about what happened, and demanding prosecutions and convictions requires an exceptional degree of commitment,” he added. “Not everyone has the strength to wage such a battle, on a daily basis, against extremely heavy odds.”

*Kanya D’Almeida was formerly the Race and Justice Reporter for Rewire.News, and has also reported for IPS from the UN, Washington DC, and her native Sri Lanka. She is currently completing an MFA in fiction writing at Columbia University, New York. This article is part of a series of stories and op-eds launched by IPS on the occasion of World Press Freedom Day on May 3.