In 1978, J.R. Jayawardena ushered in the executive presidential system in Sri Lanka as a panacea for all the nation’s woes.

By 1991, his co-architects in this venture, Gamini Dissanayake and Lalith Athulathmudali, had realized the dangers inherent in the executive presidency. They formed the DUNF not only as an opposition movement aimed at defeating President Premadasa, but also as a national movement to abolish the executive presidential system entirely.

Every president elected since, from Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga and Mahinda Rajapaksa to Maithripala Sirisena campaigned for president promising to abolish the presidency. Though these promises remained unfulfilled, under Kumaratunga and Sirisena two constitutional amendments were enacted limiting the draconian powers of the presidency. The 17th Amendment was never properly implemented while the 19th Amendment was. Although Sirisena’s administration sadly did not go through with calling for a referendum to abolish the presidency entirely, President Sirisena became our first ever head of state to voluntarily prune his own powers.

The 18th Amendment on the other hand strengthened presidential powers while removing the term limit provision, the only democratic safeguard in the system. The purpose of the bill was to enable President Mahinda Rajapaksa to contest for a third term and more. Ironically, this piece of legislation was a significant factor in his defeat in January 2015. The idea of a presidential king in all but name was an anathema to many and helped unite and rally a divided opposition.

The executive presidency was said to have been designed for J.R. Jayawardena to bring out the best in his ability to govern. In practice, it brought out the worst and led directly to anti-democratic episodes like the 1982 referendum and stripping Srimavo Bandaranaike of her civic rights.

The executive presidency was supposed to usher in an era of stability, peace and prosperity. Instead, the 43 years of its existence had been a time of relentless instability. With or without a civil war, the excesses of presidents, drunk on power, exacerbated existing problems and sparked new ones. President after president was dazzled by the trappings of their office and overwhelmed by the power of this beast. They all ultimately left office with more shame than pride. It has taken barely four decades of executive presidency to bring Sri Lanka to the brink of becoming a failed state.

Once, when Lee Quan Yew was asked what the secret was to his success, he replied “I didn’t have idiots in my Cabinet.” In Sri Lanka, politics has become the near exclusive preserve of idiots, including such blessed souls as those who wonder why we need oxygen. There have been notable exceptions, but electoral trends clearly favour the unintelligent, the uneducated and the dishonest. The Presidency has encouraged this deterioration. Time and again, executive presidents have used their excessive powers to elevate idiots and crooks whose primary qualification is their eagerness and expertise at worshiping the president.

It is abundantly clear that today’s government has not only failed, it has failed miserably and failed faster than any other in our history. We have a president who tells government officials with a straight face that his mere words are the only circulars they need. What more do you need to prove the danger of placing too much power in the hands of any single individual?

The executive presidential system enthrones a single individual as the sole leader and puts the public, civil service, police, judiciary and all other politicians at their mercy. It elevates the president like a king to be above the people and above the law. The presidency replaces the usual democratic spaces for decision making like cabinets, parliamentary caucuses and autonomous civil servants with what amounts to a royal court, packed with loyal jesters and cronies who usurp the levers of governance into a supporting cast for a one man show.

When such sycophants manage to isolate presidents and shower them with flattery, weak leaders quickly come to rely on them as they make them feel secure. They become gatekeepers, preventing Presidents from hearing alternate views, and requiring Ministers and civil servants to bow to them even to get an audience with their leader. The presidency, especially in the absence of strong and enduring institutional limitations, creates an ideal breeding ground for such sycophants and enables them to sideline professionals and career politicians. Every President finds themselves surrounded by cronies, whether business people, media moguls or obscure bagmen and their sugary charms. Policies become about people, and decisions become centred around profits for a few and not the betterment of the country.

This is why we hear of fewer and fewer successful business people today investing in their employees or infrastructure or in producing a product or service.

Today, the most successful are those who make deals, keep percentages, using political patronage to buy something cheap or sell it at a higher price, exploit suspicious tax loopholes, pump and dump schemes or illicit bond trading to make it to the top. An economy and a polity that rewards having the head of state on speed dial over honest innovation, sweat and business prowess is one that will never be taken seriously in the global marketplace.

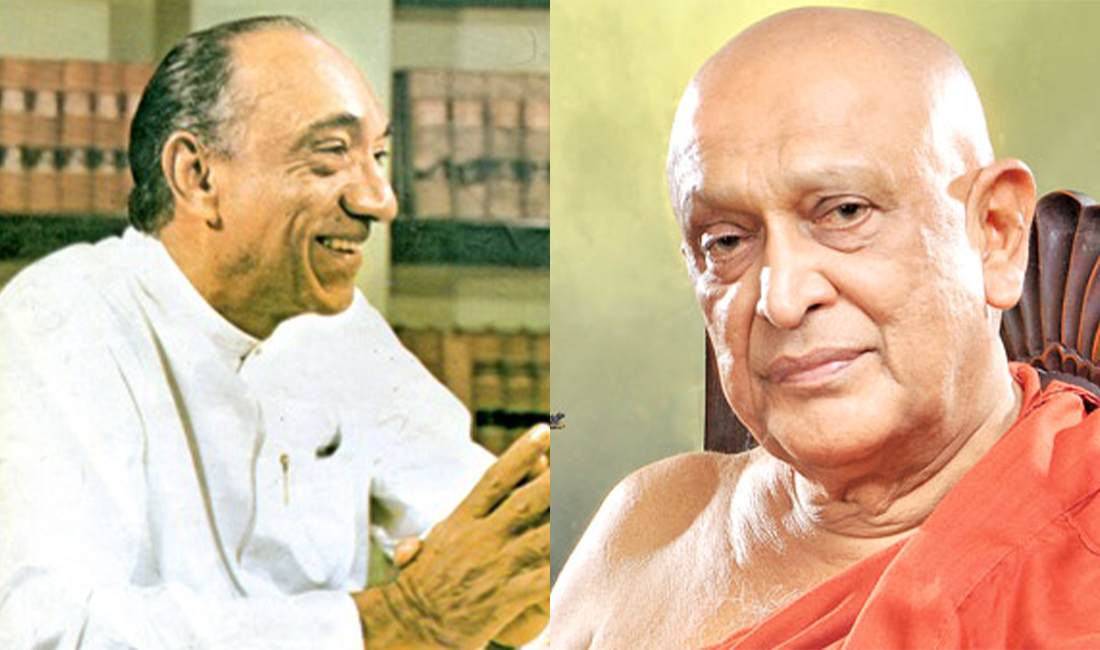

This kind of corruption was one of the key drivers for people like Ven Maduluwawe Sobitha Thero to campaign for an end to the executive presidency. Like Lalith and Gamini before him, he saw that to liberate Sri Lanka would take more than regime change. It would take radical system change. There is no point in ousting one President and replacing him or her with another who you hope will not be corrupted by the crown.

Sobitha Thero knew that the only way to get Sri Lanka on the right track was to rid us of this system altogether and replace it with one where all power is not centered in any single individual. Tragically, the government he ushered into office fell short of his vision. Still, the 19th Amendment took historic strides towards democratisation. Thanks to this landmark piece of legislation, for the first time in over 35 years our judiciary, our parliament and our public service were unshackled like a breath of fresh air. Our senior judges were not unilaterally hand-picked for appointment or promotion by a President at his whim. Instead, through the Constitutional Council, judicial appointments were made by unanimous consensus between the President, Speaker, Prime Minister, Opposition Leader, their nominees and civil society representatives.

Throughout the life of the Constitutional Council from September 2015 to September 2020, not a single judicial nominee or public servant was ever appointed by the council over objections from the opposition. Every judge was deemed suitable by the government and opposition alike. But with the 20th Amendment, once again, the president rules over the parliament, can appoint and promote judges like his chattel, and can treat public officials and career civil servants as if they are his private property.

The experience of 43 years is clear. The presidential system has weakened us as a nation, made us more divided and more unstable. It is a failed experiment. And as the calibre of men and women in politics has deteriorated, the calibre of the president too continues to deteriorate. Individuals who lack the capacity and emotional maturity to manage a kade, let alone a country, can end up wielding the power of life and death over the country and the people.

Unfortunately, all too many of our politicians have fallen under the allure of the executive presidency. They are consumed by the idea of themselves one day becoming President. They believe that they are special, that they can succeed where other presidents have failed, even though history has taught us that every president has left the country worse for wear.

If the majority of MPs feel that a prime minister is no longer performing, they could replace him or her, as so many British, Australian and Indian Prime Ministers have been dismissed from within their own parties. That constant threat gives rise to more stable, disciplined and democratic governance, rather than allowing a failed President to sit as king for years until the next election.

The executive presidency has failed. The time has come to return to our democratic roots, to a more collegiate, responsible, and accountable form of government. Sri Lanka will only thrive when we finally rid ourselves once and for all of our monarchist presidential system and replace it with a true transparent, pluralistic, liberal democracy. The power of the presidency does not flow from the heavens. The powers of the President were vested in him by Parliament and the voice of the people. Per the Constitution, these same powers can be taken away with a parliamentary supermajority of two thirds followed by a referendum. It is not a divine right, but a delegation of power by the people and their elected representatives.

It is time for a new Constitution to be drawn up that retains the unity of Sri Lanka, enshrines the rights of our citizens, and replaces the presidency with a Westminster-style government headed by a Prime Minister, along with other democratic reforms to take politics out of the process of appointing and promoting judges, police officers and civil servants.

Today’s most senior political leaders, whether in government or opposition, are too enamoured with the presidency to take the lead on dismantling it. The path forward is for those outside of politics, those whose lives, legacies and futures have been jeopardised by this system, those ordinary citizens and civil society movements that want real change. They must stand up, be counted and insist that our next leader return us to our democratic roots.

J.R. Jayawardena may have thought that the executive presidential system would save the country from impending oblivion. Now the need of the hour is for us to develop a system that can save Sri Lanka from the executive presidency itself.

Leave your comments

Login to post a comment

Post comment as a guest