Featured

The Radical Center: An Agenda for #TruePatriots

This is truly an existentialist moment for all Sri Lankans; each individual must make meaningful choices and the choices they make will define Sri Lanka's future for generations to come.

Are we to define a future for our country based on our fears and prejudices? Or are we to define a new future based on our hopes and aspirations for a better Sri Lanka for all? Are we going to allow a handful of religious and racial megalomaniacs and other fundamentalist zealots who monopolise the sensationalist media to define our future while we silently wonder if moderation and tolerance are becoming bygone values of a distant and more civilised era?

The loud and violent sounds of extremism make better news than the democratic pronouncements of the silent majority. The silence of the majority in the face of extremism, intolerance, hatred and the pseudo patriotism of the vociferous few since independence has finally culminated in the massive crisis we face today as a nation. The root causes of the crisis we are facing are economic, religious or socio political in nature and an educational system which has totally failed to provide the knowledge, experiences, critical and analytical thinking as well as values needed to meet the challenges of a developing country like Sri Lanka.

A renewal of the consensual democracy that looks beyond the adversarial politics of the left and the right is an urgent necessity. Aristotle in his treatise “Politics” of 350B.C. writes about the ‘middling element’ as the substance that bridged the chasm between the rich and the poor echoing Siddhartha Gautama from a century before. Today, as Sri Lanka stumbles from one crisis to the other the middling element may prove to be our only alternative.

A vigorous reiteration of liberal values is the need of the hour; a radical center. The center should be home to a radical commitment to liberalism and centrist values. The need now is to create a new political culture based on reviving the value systems drawn from Lord Buddha’s middle path to Mahatma Gandhi’s path of non-violence, from Nehru to Martin Luther King, from Nelson Mandela to Barack Obama.

The middle path or ‘Radical Center’ is based on the principles of democracy, freedom, equality and justice as the four pillared foundation for a just, caring and prosperous society. Although many may say that a radical center is a contradiction in terms, a radical recommitment to liberal democratic principles is an urgent necessity along with the courage of one's convictions even to wage a non-violent struggle if and when necessary to protect and achieve these values. The Radical Center is a platform of moderation providing the silent majority to oppose and fight authoritarianism, racism and all other forms of extremism actively and vigorously.

The ‘Radical Center’ entails the creation of a centrist middle way where dissenting voices and opinions from every part of the political spectrum would have a place within a democratic framework of decentralised governance. It is a system where diversity in all its manifestations is celebrated; the years of deep mistrust between the different communities must lose its sting within a non-violent, democratic framework where pluralism and secularism flourish. The radical center should show the intolerant that those they hate are in fact, quite similar to themselves and have the same dreams and aspirations as well as the same fears and concerns as human beings. The radical center should be the point where all Sri Lankans can discover their common humanity going beyond the boundaries of race, creed and caste.

All right thinking people across Sri Lanka must break their silence and unite to protect democracy. The tyranny of the few can only be defeated if the silent majority - the true patriots - wakes up from their somnambulist stupor to say ‘enough is enough.’ True to the saying by Samuel Johnson, patriotism in Sri Lanka has now become the ‘last refuge of the scoundrel’; patriotism as encouraged today is thinly veiled racism and overzealous chauvinism which has been the main cause of our downhill journey since independence.

Patriotism needs to be redefined to reflect the goals and aspirations of a modern Sri Lanka rejecting the feudal/tribal attitudes and ‘big frog in a small well’ mindset of the post ’56 era. While celebrating the diversity and glory of our respective ancient cultures and religions, the new patriots of Sri Lanka - nationalistic and cosmopolitan - must unite to march hand in hand with the rest of the world towards freedom, happiness and prosperity.

We believe.....

Political parties should seal social contracts before religious leaders & chief justices

Instead, wealth inequality has not improved in the last 5 years and income growth has slowed across the board except for the wealthiest. No matter how much assistance the government gives, there will always remain a segment of the population that cannot catch up. This is when social expenditure of the government must increase.

These ideals echo the aspirations of our early leaders who enshrined the values in the pledge all Singaporean students recite by heart daily. These are also the values encapsulated in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which the United Nations’ General Assembly, which Singapore is a part of, has agreed to support.

We urge the government this national day to help citizens overcome various injustices, whether economic, social, political or cultural and truly realize the values in our national pledge”.

In Sri Lanka’s Elections, a Rajapaksa Win Would Seal Democracy’s Fate

In the first few months of Gotabaya’s presidency, the Rajapaksas—Sri Lanka’s most prominent political family—moved swiftly to centralize power, with Gotabaya immediately appointing Mahinda as prime minister. The two other Rajapaksa brothers, Chamal and Basil, hold important political positions as well; the former is a Cabinet minister, and the latter is both Gotabaya’s “chief strategist” and the national organizer of the Sri Lanka People’s Front, the Rajapaksa-backed political party relaunched in 2016. Gotabaya has also surrounded himself with current and former members of the Sri Lankan military who have been credibly accused of serious wartime abuses during the country’s civil war with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, also known as the Tamil Tigers.

With the return of this powerful family and their supporters to power, a climate of fear has returned for Sri Lanka’s dissidents, ethnic and religious minorities, and others. Under Gotabaya’s leadership, the space for dissent has shrunk and self-censorship has grown, while surveillance, repression and intimidation have been on the rise. In a critical statement last month, Clement Voule, the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and association, warned that lawful peaceful assemblies were reportedly “prevented from taking place, or … met with physical and verbal violence at the hands of individuals, without public intervention.”

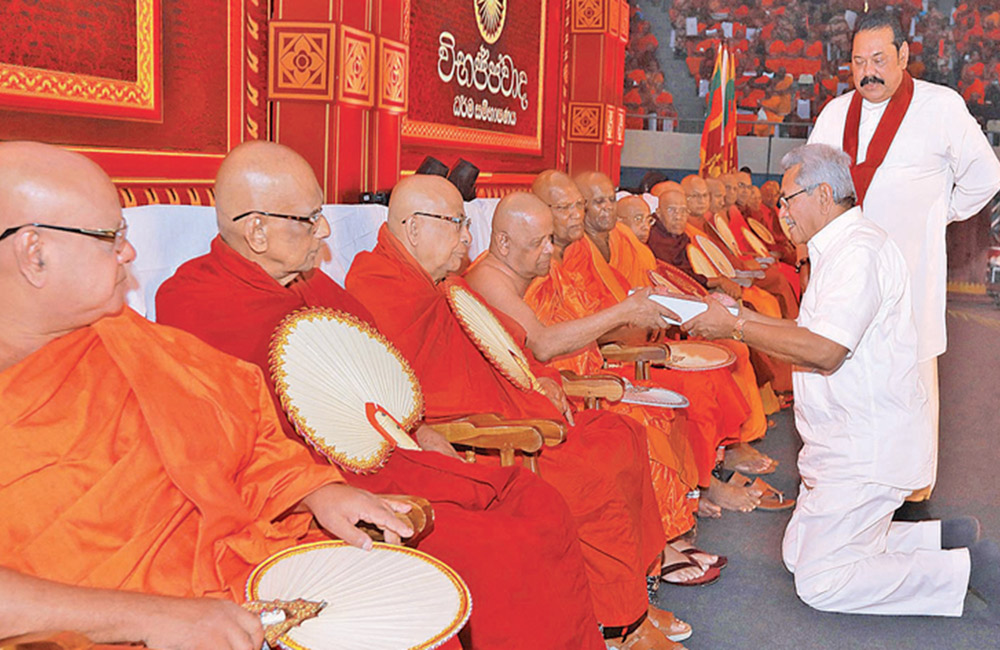

But the Rajapaksas are not just unapologetic authoritarians; they are also enthusiastic Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalists, enforcing a view of Sri Lanka as a Sinhalese-Buddhist nation, to the exclusion of minority populations. Since November, Gotabaya and his allies have further militarized civilian institutions and stoked Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalism to consolidate political power. Fear of discrimination and repression has returned to the island nation, whose long civil war ended brutally in 2009.

In a few weeks, on Aug. 5, Sri Lankans will once again go to the ballot box to take part, finally, in parliamentary elections that have been delayed twice because of the coronavirus pandemic. In Sri Lanka, both the president and the prime minister wield executive power. If the Rajapaksa-backed coalition, the Sri Lanka People’s Freedom Alliance, is able to secure a majority of seats in Parliament and keep the prime ministership, there will be no significant check on Gotabaya’s rule.

The Rajapaksas are likely to use that vast political power to dismantle Sri Lanka’s institutions, rework the constitution and perpetuate a hard-line, nationalist agenda. More than a decade after the end of its civil war, and five years after an election that had seemed to put it on a more firmly democratic path, Sri Lanka is haunted again by the specter of growing oppression. The war may be over, but the ethnic conflict and the pain that emanates from it have persisted. With the Rajapaksas back in charge—disparaging transitional justice efforts and encouraging political, ethnic and religious tensions—Sri Lanka won’t be able to build a durable peace.

A Rajapaksa Resurgence

Some Western observers attributed Gotabaya’s electoral victory to last year’s Easter Sunday bombings, the horrific suicide attacks that targeted Christian churches and luxury hotels across the country, killing 269 people. The attacks, which prompted criticism of the previous government’s intelligence collection, security provision and political infighting, certainly helped the Rajapaksas in their election campaign. Gotabaya announced his candidacy just days after the attacks, promising to return stability to the country. Nevertheless, the degree to which the bombings changed Sri Lankan politics has been largely overstated.

The bombings didn’t save the Rajapaksas from political defeat; rather, the family had been steadily gaining ground for years. After overseeing the devastating end of the country’s civil war and then steering Sri Lanka toward authoritarianism, Mahinda Rajapaksa lost the presidency in 2015 to Maithripala Sirisena, a former health minister in Mahinda’s Cabinet and longtime member of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party. Mahinda lost in large part because of corruption allegations and the growing sense that he was taking the country along a dangerously authoritarian path. But the Rajapaksas, especially Mahinda, continued to be influential players on the political scene. The Rajapaksa-backed Sri Lanka People’s Front dominated local government elections in February 2018. Then, in October 2018, with the Rajapaksas poised to return to power in the next round of national elections, Sirisena illegally appointed Mahinda as prime minister in an effort to preserve his own future and regain political salience. But the move set off a constitutional crisis that lasted for more than seven weeks. While Mahinda eventually “resigned” from the post, the debacle underscored both Sirisena’s feckless leadership and Mahinda’s continued relevance.

In the leadup to last November’s presidential election, Sri Lankan voters had become extremely frustrated with Sirisena’s leadership. Under Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, the coalition government—led by Sirisena’s Sri Lanka Freedom Party and Wickremesinghe’s United National Party—was plagued by infighting, incompetence and missed opportunities. It promulgated an ambitious, wide-ranging reform agenda—including improved governance, constitutional reform, transitional justice and economic adjustments—but failed to deliver on almost all of it.

Gotabaya, in response, capitalized on his credentials as a military man known for getting things done, pointing to his role in defeating the separatist Tamil Tigers and ending Sri Lanka’s civil war. He had served as secretary to the Ministry of Defense from 2005 to 2015, in his brother’s government, through the end of the civil war, and today both Gotabaya and Mahinda are still greatly admired by many Sinhalese-Buddhists as courageous leaders and war heroes. Gotabaya almost certainly would have won without the Easter bombings, and a victory by his opponent, Sajith Premadasa, the ruling coalition’s candidate, would have constituted a big upset.

Since returning to office, Gotabaya has ruled ruthlessly, causing consternation among human rights activists, minority groups and others. Still, after years of rudderless coalition government, the Sri Lankan electorate yearned for decisive leadership, and Gotabaya and his family remain quite popular among Sinhalese voters.

The Ethnic Conflict

At the heart of Sri Lanka’s civil war was a longstanding ethnic conflict over state power, a conflict that still hasn’t been resolved today. Ethnic Sinhalese, most of whom are Buddhist, constitute the overwhelming majority—about 75 percent—of the country’s population. Tamils and Muslims are the largest minority groups. Since Sri Lanka became an independent country in 1948, Sinhalese have always dominated the state’s institutions, including the police and the military. In contrast, Tamils, who make up just 11 percent of the country’s population, have faced widespread discrimination. They have had their land forcibly appropriated by the state and their language denigrated. They have been deprived of educational and employment opportunities through discriminatory policies. In 1958, 1977, 1981 and 1983, mobs of Sinhalese targeted Tamils in violent pogroms. Black July, as the series of riots and pogroms against Tamils that occurred in July 1983 is known, led to thousands of deaths and mass displacement, and is widely considered to be the start of the civil war.

The rise of Tamil militancy throughout the 1970s culminated in the emergence of the Tamil Tigers, which fought an insurgency against the government from the early-1980s until 2009, seeking to create a separate Tamil state in northern and eastern Sri Lanka. The Tigers were well-resourced, disciplined and ruthless. They pioneered suicide bombing, conscripted child soldiers and committed other serious human rights violations.

Over the course of the conflict, both sides committed serious wartime abuses. But during the final campaign overseen by Mahinda and Gotabaya, Sri Lankan government forces are credibly accused of a range of abuses, including the deliberate shelling of hospitals, enforced disappearances, targeting civilians intentionally and mass rape. By the time the civil war ended, massive numbers of Tamil civilians had been killed, as well as almost all the Tigers’ leadership, who are widely and credibly thought to have been killed extrajudicially, both throughout the war and during its bloody finish. Sri Lankan soldiers remove debris after anti-Muslim riots in Digana, Sri Lanka, March 6, 2018 (AP photo by Pradeep Pathiran).

Sri Lankan soldiers remove debris after anti-Muslim riots in Digana, Sri Lanka, March 6, 2018 (AP photo by Pradeep Pathiran).

In the years that followed the end of the fighting, rather than seeking to reconcile a fractured country, Mahinda Rajapaksa prioritized economic growth and governed increasingly as an autocrat. The impunity that characterized the end of the war carried over into the postwar period, and Sri Lanka became one of the most dangerous places in the world for journalists. Self-censorship became more common, as the state cracked down on civil society and imposed new limits on free speech. Activists and others at odds with the state were targeted by notorious gangs of kidnappers, many of them snatched off the street into white vans. Corruption and nepotism were huge issues, with Mahinda, his brothers Gotabaya and Basil, his sons, and high-ranking government officials accused of stealing a total of $18 billion from the country’s coffers, among other concerns.

To defeat Mahinda at the polls, his opponents formed a broad and diverse coalition to back Sirisena, and snatched a surprising victory from the rising authoritarian. Sirisena’s campaign focused largely on curbing corruption and improving governance. Although the government subsequently committed to a broad transitional justice agenda later that year, there was never any electoral mandate for that program.

Throughout Sirisena’s presidency, ethnic tensions remained a significant issue. Muslims were targeted by the state and others, including in massive riots in 2018, when Sinhalese-Buddhist mobs burned and vandalized mosques and homes and attacked scores of Muslims, killing at least two. In the wake of the Easter bombings, too, police and the military reportedly stood by as mosques and Muslim-owned shops and homes were torched and vandalized. There is a widespread perception that Sri Lanka’s state security personnel allowed the violence to happen—and, yet again, perpetrators have not been held accountable.

The lines between state-led violence and community-driven attacks are often blurred in these kinds of communal riots in Sri Lanka. State actors have actively participated in pogroms going back decades, and in some instances, state security personnel have reportedly acted as orchestrators or organizers. On numerous other occasions, state security personnel looked the other way and allowed community-driven violence to occur or continue. In all these cases, minority communities are sent a clear message: The law is not applied equally in Sri Lanka, and the state is unwilling, or unable, to protect them.

When the surges of violence die down, Tamils and Muslims are left to contend with other types of discrimination. In the wake of the Easter attacks, non-Muslim Sri Lankans boycotted Muslims places of business, and more recently they have circulated false rumors blaming Muslims for spreading the coronavirus. The state, for its part, has targeted Muslims unjustly under the pretext of an investigation into the Easter bombings. Further, the government’s decision to enforce “mandatory cremation” for coronavirus victims, despite the fact that cremation is forbidden in Islam, has reinforced the widespread sense that an anti-Muslim campaign—one that enjoys the backing of the state—is underway.

Meanwhile, the Northern and Eastern Provinces, the historically Tamil regions where most of the fighting occurred during the war, remain heavily militarized. The military, which is almost entirely Sinhalese, regularly intervenes in civilian life there, at times even determining where Tamils can live. It also plays a large role in the agricultural and tourism sectors, depriving civilians of sorely needed economic opportunities. To be sure, the militarization of civic space is an issue throughout the country, as postwar demilitarization has yet to occur. But it’s noticeably worse in these provinces, fueling resentment among the civilian population and making Tamils feel like they are essentially living under military occupation.

Gotabaya’s new government, meanwhile, has made it clear that it truly does not care about symbolic gestures of unity, preferring instead to send the message that Sri Lanka is a land for Sinhalese Buddhists. On Feb. 4, Sri Lanka’s Independence Day, the government decided against including a Tamil version of the national anthem in its celebrations, a practice introduced by the previous government as a show of good faith to the Tamil minority. At the same time, Gotabaya has extended policies that seek to establish Sri Lanka’s identity as an exclusively Sinhalese-Buddhist state. A continued process of “Sinhalization” in historically Tamil areas is supplanting local heritage with Sinhalese culture, through government programs to change the names of villages, build Buddhist shrines at Hindu religious sites, and offer land grants to Sinhalese migrants. Sinhalization is also taking place in the Eastern Province, which includes significant Tamil, Muslim and, more recently, Sinhalese populations. The military’s prominent and sustained presence in these locations further strengthens this process of cultural transformation.

Discarding Transitional Justice

In 2015, Sirisena’s government co-sponsored a U.N. Human Rights Council resolution on Sri Lanka that stressed the need for a comprehensive transitional justice agenda, including a truth commission, an accountability mechanism and offices to handle both disappearances and reparations. The move inspired hope that the country’s new leaders would pursue the postwar reconciliation processes Mahinda had neglected.

Yet in the years that followed, the government sought and was granted two extensions on its 2015 commitments, in the form of other co-sponsored resolutions. Gotabaya has gone even further: In February, his government announced that Sri Lanka would be withdrawing from the resolution entirely.

The reality is that Sri Lanka’s ambitious transitional justice process had been in trouble for years. It’s far from clear that the previous government, outside of a small collection of well-meaning individuals, ever intended to comply with those U.N. resolutions. The previous government did succeed in establishing an Office on Missing Persons and an Office for Reparations, although these bodies have yet to produce major results. The Office on Missing Persons, for example, still has not traced a single missing person. Besides, the body is not empowered to legally hold perpetrators to account.

The current administration has stated that it will pursue reconciliation on its own terms, yet such an assertion lacks credibility. Under Gotabaya, there’s been no real talk of establishing a legitimate truth commission or, most controversially, an accountability mechanism. On the contrary, military officers who are alleged war criminals, such as Maj. Gen. Shavendra Silva, continue to be promoted; Silva is currently leading the government’s coronavirus response efforts. Relatedly, Sri Lanka has shown no signs that it has any interest in reforming its security sector, something that’s urgently needed. After all, Sri Lankan security personnel are responsible for ongoing acts of torture and sexual violence; absent real reform, these extremely distressing trends will undoubtedly continue in the coming years.

The truth is that the Sri Lankan government has never adequately explained the processes of the U.N. Human Rights Council to the Sinhalese majority—nor has it explained the urgent need for transitional justice and building a durable peace. The loudest voices making this case have come from civil society efforts, including the Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms, a group of civil society leaders that carried out wide-ranging public consultations pertaining to transitional justice mechanisms. Despite the fact that the task force was appointed by Wickremesinghe, its findings were largely ignored by the coalition government.

To this day, many Sinhalese lack an understanding of the importance of transitional justice and the need to finally resolve the ethnic conflict. Why, they ask, should the majority community move to address Tamil grievances when the Tigers lost the war? These Sri Lankans view Sinhalese soldiers not as possible human rights violators to be investigated, but as war heroes who, having defeated an insidious terrorist insurgency, should be venerated. According to this view, holding Sri Lankan military personnel accountable would not just tarnish the reputation of the military, it would tarnish the reputation of the entire country, and any attempts to do so, or to address wartime abuses of power more generally, are looked at askance. Tamil women hold portraits of missing relatives to advocate for a post-war reconciliation process, in Colombo, April 6, 2015 (AP photo by Eranga Jayawardena).

Tamil women hold portraits of missing relatives to advocate for a post-war reconciliation process, in Colombo, April 6, 2015 (AP photo by Eranga Jayawardena).

“It has been fed into the psyche of the Sinhalese that the Tamil Tigers were terrorists—whatever it shall mean—and they were trying to divide a Sinhala-Buddhist country, to the prejudice of the Sinhalese,” said C.V. Wigneswaran, the secretary general of the recently created Tamil People’s National Alliance who is running for a seat in parliament, in an email interview. “The irony of all this is if the Sinhalese feel so strongly about the innocence of their soldiers, they should allow impartial investigation into the conduct of the Sri Lankan soldiers during the war, so that they could clear their names,” Wigneswaran adds. Nevertheless, Gotabaya, too, has promised to protect the nation’s “war heroes.”

Yet as long as the country fails to follow through with a credible and comprehensive transitional justice program, a return to another period of open ethnic violence at some point in the future cannot be ruled out. Despite those risks, the prevalence of Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalism makes it politically fraught for any party or leader to be seen making concessions to minority communities. These dynamics mean that talking about issues like Tamil and Muslim rights, or a more inclusive Sri Lanka, would require extraordinary political courage. Worse still, political calculations aside, there is little evidence to suggest that Sinhalese political elites would even like to implement these bold changes.

Parliamentary Elections Amid COVID-19

The coronavirus pandemic is only making all of this worse. Gotabaya dissolved Parliament on March 2, six months ahead of schedule, to pave the way for an early election that was initially slated for April 25. Less than three weeks later, the National Election Commission postponed the election due to concerns over COVID-19, first to June 20 before again being moved to August. Though it’s unlikely, there are concerns that the election will be postponed again after a recent spike in coronavirus cases raised alarms.

If elections proceed on Aug. 5, Sri Lanka will have gone more than five months without a functional Parliament. That is extremely worrisome and bodes ill for the country’s democracy. Sri Lanka’s constitution states that a new Parliament must be sworn in within three months of the old one being dissolved, meaning by June 2 in this case. Various civil society groups and opposition parties filed petitions protesting the postponements on constitutional grounds, but Sri Lanka’s Supreme Court dismissed all the cases.

Some political observers have suggested that Gotabaya should reconvene the Parliament he disbanded in March, an option he has rejected largely because he doesn’t want parliamentary oversight over the executive. He can wield more power as long as the current Parliament remains dissolved. The fact that Gotabaya has been able to rule without checks on his authority for so long sets a terrible precedent for the country’s messy and majoritarian democracy.

Gotabaya’s government has used this power to launch a heavy-handed response to COVID-19, relying excessively on the military. Its leadership in the coronavirus response has led to unnecessary arrests, detentions and the further shrinking of civic space. A senior human rights activist, speaking on the condition of anonymity out of concerns for their safety, told me that although Tamils residing in the north knew that daily life for civilians would worsen during a Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidency, “the pandemic has fast-tracked this, unfortunately. Militarization is in your face now.”

In this political context, former Prime Minister Wickremesinghe’s United National Party could have a pivotal role to play, were it not in disarray. After a bitter feud at the top, the party selected Premadasa over former Wickremesinghe as its presidential candidate in last year’s election, and the rivalry between the two men has persisted since his defeat. As a result, Premadasa is now leading the United People's Front, a new political alliance that includes a breakaway group from the United National Party and is competing for its own seats in parliament.

A weak and rudderless United National Party amid a divided opposition is bad news for proponents of democracy, making it easier for the Rajapaksas to win more control of Parliament. To have any chance of serving as a significant check on the rule of the Rajapaksas, Sri Lanka’s unwieldly political opposition would need to remain united. Yet the space to create such a movement seems far narrower now. To be clear, even if the United National Party or others opposed to the Rajapaksas’ rule regained power, the longstanding issues pertaining to the ethnic conflict would almost certainly continue to be ignored. That said, continued Rajapaksa rule will make the situation even worse.

The Road Ahead

The early days of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidency have done nothing to allay widespread worries, in Sri Lanka and internationally, about how he would govern. He has clamped down on dissent, and his government has continued to disregard the root causes of the country’s unresolved ethnic conflict. Healing Sri Lanka’s war wounds will require an adequate transitional justice program, including a truth commission, an accountability mechanism, some form of power-sharing arrangement with minority ethnic groups and meaningful reparations. None of that seems viable right now. Even worse, the Rajapaksas are deepening the country’s already persistent ethnic and religious divides.

There’s a real possibility that the Rajapaksas and their allies will emerge from next month’s election with a two-thirds majority in Parliament. If that happens, they will be able to change the constitution at will, making it even easier for them to dismantle the country’s institutions, and to do so with a veneer of legitimacy. Even if they do not pass that two-thirds threshold, it’s widely believed that the Rajapaksas will still have a comfortable majority to tighten their grip on power.

As flawed as its governance has been, Sri Lanka has always been a democracy, albeit on majoritarian terms. Mahinda Rajapaksa took the country to the edge of full-on authoritarianism as president. His brother Gotabaya, who also proudly espouses Sinhalese-Buddhist nationalism, could go even further. The future of Sri Lankan democracy is now very much at stake.

*Taylor Dibbert is an adjunct fellow at Pacific Forum. Follow him on Twitter @taylordibbert.

UNHRC session crucial for Sri Lanka's reconciliation

The 43rd session of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), which runs until March 20, will be crucial for Sri Lanka as the government has decided to withdraw co-sponsorship of resolutions 30/1, 34/1 and 40/1 under which the government undertook accountability and reconciliation after the civil war ended in May 2009.

In her statement to the UNHRC, High Commissioner Michelle Bachelet conceded that while some progress has been made in promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights, she was concerned about the inability of the government to deal with impunity and to reform institutions, which may trigger a recurrence of rights violations.

She urged the UNHRC to closely monitor developments in Sri Lanka and called for full implementation of the resolutions.

Meanwhile, the government of Sri Lanka on Feb. 20, while withdrawing co-sponsorship of resolution 30/1, pledged to continue to work with the UN and seek capacity building and technical assistance in keeping with domestic priorities and policies. It also announced its intention to work toward closure of the resolution in cooperation with the UN.

Sri Lanka has until March 2021 to implement its commitments to the UNHRC, especially regarding the creation of a war crimes investigation panel.

Let us review the period of the previous unity government from Oct. 1, 2015, up to the appointment of a new government on Nov. 16, 2019.

As Bachelet made clear to the UNHRC, some progress has been made in promoting reconciliation and accountability and human rights in line with the co-sponsored resolution.

A step in the right direction and one that was absolutely essential for the accountability process was the creation of the Office of the Missing Persons as well as the Office for Reparations.

“The commitments made by the previous government had contributed to the lapses that resulted in the Easter Sunday attacks in April 2019,” the government stated while declaring the unilateral decision to withdraw from co-sponsorship of the resolution.

A Commission for Truth, Justice, Reconciliation and Non-Recurrence was not established, though the government agreed to formulate mechanisms under the provisions of the constitution without the participation of international judges and proposed hybrid special courts. These were not established during the period of the unity government as the then prime minister and president were acting against each other in an ugly power consolidation process.

As promised, the reform agenda, the new charter, reforming the electoral process and solving the national question of federalism versus autonomy were not resolved.

Though they promised to abolish the executive presidency as well as set up of independent commissions, only the 19th amendment of the charter was passed by parliament on April 28, 2015 by an overwhelming majority of 215 votes. This paved the way to reducing the powers of the executive presidency and strengthen parliament and must rank among the success stories.

Reformist agenda

The impact of the 19th amendment has had on Sri Lankan society is enormous and self-evident. The civil service, police and judiciary are independently exercising their powers with renewed vigor due to the enabling situation created by constitutional reforms.

President Maithripala Sirisena in October 2018 sacked Prime Minister Ranil Wickramasinghe and appointed Mahinda Rajapaksa and dissolved parliament. However, due to the powers granted by 19th amendment, the judiciary declared these moves illegal and reinstated Wickremasinghe. That is how the reformist agenda was carried out during the previous regime.

It is interesting to know how the question of accountability came to the fore. When the conflict finally ended in 2009, President Rajapaksa met with UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon and agreed to an accountability probe. But Rajapaksa did not listen to the international community’s call for wartime accountability until he was defeated in January 2015.

The change of government averted possible international sanctions over Rajapaksa’s failure to adequately deal with war crimes. Some claim that up to 40,000 Tamils were killed in the final months of the civil war.

Meanwhile, the Sri Lankan delegation to UNHRC meeting in Geneva left on Feb. 25. Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena officially informed the council on Feb. 26 of the government’s decision to withdraw from co-sponsorship of resolutions 30/1, 34/1 and 40/1.

“Procedurally, in co-sponsoring resolution 30/1, the previous government violated all democratic principles of governance and the resolution seeks to cast upon Sri Lanka obligations that cannot be carried out within its constitutional framework and it infringes the sovereignty of the people of Sri Lanka and violates the basic structure of the constitution and that is why Sri Lanka was prompted to reconsider its position on co-sponsorship.”

The Sri Lankan government has six months to devise new strategies before the rights body meets in September.

The Tamil minority is uneasy with the situation created by withdrawing co-sponsorship of the resolution calling for an investigation into alleged rights violations committed during the long civil war. Civil society organizations and religious leaders should address these issues as soon as possible.

Though the government has withdrawn co-sponsorship of the resolution, it is effective until March 2021. The government will have to face the UNHRC again in September. If the obligations set by the rights body are not fulfilled, an embargo could ensue.

“Domestic processes have consistently failed to deliver accountability in the past and I am not convinced the appointment of another Commission of Inquiry will advance this agenda. As a result, victims remain denied justice and Sri Lankans from all communities have no guarantee that past patterns of human rights violations will not recur,” Bachelet said in her address to the UNHRC on Feb. 27.

The reaction of the international community will become known to the public during the coming days of the UNHRC meeting.

As the government has asked the council to announce its intention to work toward closure of the resolution, one wonders whether there will be any accountability and reconciliation process in the future.

Kingsley Karunaratne is administrative secretary of the Rule of Law Forum, which is affiliated to the Asian Human Rights Commission. His organization works for fundamental redesigning of justice institutions to protect and promote human rights. The views expressed in this article are those of the author.

Is Sri Lanka Becoming a De Facto Junta?

Sri Lanka's President Gotabaya Rajapaksa (center) gestures during Sri Lanka's 72nd Independence Day celebrations in Colombo on Feb. 4. ISHARA S. KODIKARA/AFP via Getty Images

Sri Lanka's President Gotabaya Rajapaksa (center) gestures during Sri Lanka's 72nd Independence Day celebrations in Colombo on Feb. 4. ISHARA S. KODIKARA/AFP via Getty Images

Rajapaksa won the election in November, taking the seat once held by his brother. In February, at his first Independence Day celebration, he declared, once again, his respect for human rights: “The responsibilities of the civilian and military establishments need to be clearly understood, and we must always remember that citizens have individual as well as collective rights.” Dressed in civilian attire, Rajapaksa nonetheless donned badges awarded to him during his long military career. Perhaps it was a hint of what was to come.

In the last several months, Rajapaksa has embarked on rapidly militarizing the state administration. He has appointed a number of retired military officers to key positions in the civil administration, and his government has moved more than 30 agencies under the remit of the defense ministry.

Moves such as his lengthy dissolution of Parliament and his shock pardon of a sergeant recently sentenced to death for killing eight civilians, including children, during the country’s civil war suggest a disdain for the legal system and constitution. With each passing day, Sri Lanka appears to be edging closer toward military totalitarianism.

Rajapaksa’s authoritarian transition should not be surprising. A brother of Mahinda Rajapaksa—who served as president from 2005 to 2015 and has since been appointed as prime minister—Gotabaya Rajapaksa is best known for defeating the separatist Tamil Tigers and bringing an end to a three-decade-long civil war in 2009. An estimated 40,000 Tamil civilians died during the final months, and as many as 100,000 civilians from both sides were killed since the start of the war in 1983. Tens of thousands more forced disappearances took place during and after the civil war, and efforts to provide justice for the victims have stalled. Earlier this year, the government withdrew altogether from a co-sponsored United Nations Human Rights Council resolution to investigate and prosecute those responsible for civil war atrocities.

There is little chance that such justice will be forthcoming. Speaking at a remembrance ceremony for fallen soldiers in Colombo on May 19, Rajapaksa vowed to protect those who fought in the civil war and said that he would not hesitate to withdraw from international organizations that target them. Already, the president appears to be signaling that security forces and police can act with impunity. In March, Rajapaksa pardoned and released Sunil Ratnayake, a former Sri Lankan army staff sergeant convicted of the brutal murder of eight Tamil civilians, including three children—one of the very few soldiers to face trial.

Rajapaksa himself has faced, and denied, repeated accusations of war crimes and atrocities. In his eight months in office, he has appointed a series of military commanders who have been accused of serious alleged international crimes during the civil war—commanders who currently hold high-level government positions. Sri Lanka is “intentionally and deliberately promoting … impunity by appointing alleged war criminals to positions of power,” the International Truth and Justice Project said in a recent investigation.

Former senior military officials have been put in charge of the Ministry of Law and Order, the Ministry of Human Resources, the Ministry of Finance, and, now, with the COVID-19 crisis, the Ministry of Health. In addition to appointing ex-military officers into civil sector positions, the government has also started handing civil administrative functions to the military. Reporting by the Tamil Guardian shows that at least 37 agencies including the police, the telecommunications regulator, and the nongovernmental organization secretariat have been wholly placed under the Ministry of Defense. Separately, the president has set up at least seven new task forces, with vague and far-reaching mandates, staffed heavily by military officials.

Recent wrangling in Parliament, meanwhile, shows the extent to which Rajapaksa is willing to bend Sri Lanka’s constitution to his will. On March 2, Rajapaksa legally (but six months ahead of schedule) dissolved Parliament, setting the election date to April 25. Since then, in response to the coronavirus crisis, he has repeatedly pushed the date back, with elections now planned for Aug. 5. The constitution mandates that Parliament meet again within three months of its dissolution, but Rajapaksa has denied requests by opposition parties urging to reconvene. The Supreme Court has also refused petitions to order Parliament be reconvened and has ignored challenges on the delayed poll date, although it has yet to explain its reasoning.

Yet reconvening Parliament is now even more urgent thanks to the coronavirus pandemic. The only legal way for the government to formalize budgets for fighting the virus is to go through the legislature. Finances are now being appropriated and disbursed by the President’s Fund, which is allocating nearly $2 billion in pledged foreign assistance to combat the coronavirus—though without parliamentary oversight there is little transparency to the process.

While Rajapaksa’s machinations over the past months may have drawn withering criticism from watchdogs and rights activists, it is unclear how this has affected his popularity among the wider public. Rajapaksa is hoping the Aug. 5 vote will seal his grip on power after he won last year’s election on a seemingly popular national security agenda. If his Sri Lanka People’s Front party can obtain a two-thirds majority, he has promised that one of his first efforts will be to repeal the 19th Amendment, which limits executive power.

Beyond Rajapaksa's visit - are India and Sri Lanka on the same page?

By Dr. Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan

Sri Lankan Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa just completed a five-day trip to India, making it his first foreign trip since his appointment as prime minister in late November 2019. While the trip highlighted some areas for collaboration between the two sides, it also left broader questions lingering about the future direction of ties.

By all accounts, Rajapaksa’s visit appears to have been a successful one. For instance, Mahinda touched the right cords in New Delhi even on sensitive issues by stating that developments relating to Jammu and Kashmir and Article 370 were India’s internal affairs. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, for his part, said in his press statement that he appreciated Sri Lanka’s importance not only to India but to the entire Indian Ocean Region. He added that “stability, security and prosperity in Sri Lanka” is an essential element in ushering peace and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.

In line with the “Neighborhood First” approach and the “Sagar” doctrine, Modi went on to say that New Delhi attaches “a special priority” to its relations with Colombo, which will no doubt be welcome. Sri Lanka also appears to be satisfied with the comfort level that exists between Modi and Rajapaksa and the pace of the relationship.

But there may be some disagreements that remain. For instance, according to reports citing diplomatic sources, Sri Lanka wants to see “cooperation and progress in SAARC,” whereas India believes that all efforts to strengthen regional cooperation should be channeled to the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC). Even though Rajapaksa is not thought to have raised the SAARC issue with Modi, he raised this point in an interview with The Hindu where he made a case for SAARC saying “we have already gone a considerable distance with building SAARC and that should be continued.”

Sri Lanka pushing the SAARC is understandable – a Sri Lankan diplomat, Esala Weerakoon, has been appointed to be the next Secretary General of the SAARC Secretariat, and Sri Lanka would like to show some progress in the association. On March 1, 2020, Weerakoon will be taking charge of SAARC from Amjad Hussain B. Sial, his Pakistani predecessor, who has held the post since 2017. Given this development, Sri Lanka is believed to have urged the Indian leadership to “at least restart the process of discussion on SAARC” but clearly it will be difficult getting India on board.

In addition to official meetings, Rajapaksa also reached out to the media and aired the Sri Lankan interest in some of the infrastructure projects on the bilateral agenda. Rajapaksa was categorical that Sri Lanka will no longer grant important projects such as the Mattala airport to other countries. Mahinda added that projects already approved by Wickremasinghe will be stopped. He also said that “his government has a firm policy on not allowing any national resources to be given to foreign control.” However, at the same time, Rajapaksa seemed upbeat about the LNG project as well as the Eastern Container Terminal in Colombo, which will see joint investment by India and Japan.

On the debt repayment issue with China, Rajapaksa defended the Chinese by saying Beijing helped Colombo in Sri Lanka’s post-war reconstruction and development efforts. He went on to note that the debt toward China is only 12 percent of the overall external debt and that the funds from China was used for developing infrastructure. He faulted the previous government for giving away strategic real estate in the Indian Ocean such as Hambantota for the debt. Defending China of course probably earned Rajapaksa some brownie points with Beijing and gave some balance to Sri Lanka’s external alignments.

To be sure, Rajapaksa also stated India is a “relation” whereas others are friends. But he was uncomfortable with concepts like the “Indo-Pacific,” which he did not use though it was used by Modi, as well as with groupings like the Quad. Colombo clearly does not want to takes sides against China.

Of course, the thorny Tamil issue was also highlighted during Rajapaksa’s visit. In fact, Modi in his press statement said, “I am confident that the Government of Sri Lanka will realize the expectations of the Tamil people for equality, justice, peace, and respect within a united Sri Lanka. For this, it will be necessary to carry forward the process of reconciliation with the implementation of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka.”

However, during the media interview with the Hindu, Rajapaksa made no commitment on how the 13th amendment will be implemented, except to say no solution to the problem will happen without it being acceptable to the majority community. He elaborated on the point saying “We want to go forward, but we need to have someone to discuss, who can take responsibility for the [Tamil] areas. So the best thing is to hold elections, and then ask for their representatives to come and discuss the future with us.” Rajapaksa is hoping for a win in the upcoming parliamentary elections in April and thereafter to hold provincial elections that could pave way greater engagement with the Tamil population.

While the Rajapaksa visit has ended successfully, among the tricky issues, one that New Delhi needs to focus on is to find a balance between Sri Lanka’s interest in SAARC and the Indian preference for BIMSTEC. Given India’s larger strategic footprint across the Indo-Pacific and India’s Act East policy, BIMSTEC makes sense. But Sri Lanka is not keen. India needs to work on building support for it in other capitals in South Asia. Also, New Delhi has to be able to offer economic opportunities for these countries to make BIMSTEC attractive. Otherwise it will be seen as just empty anti-Pakistan rhetoric with no real worth for the small countries in the region. More generally, India should also be careful not to alienate the smaller countries who might not want to antagonize China.

*Dr. Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan is Distinguished Fellow and Head of the Nuclear and Space Policy Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), one of India’s leading think tanks.Previously, she held stints at the National Security Council Secretariat, where she was an assistant director, and the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses New Delhi, where she was a research office.

On Hejaaz Hizbullah: The latest victim of Sri Lanka’s draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act

The health officials never visited, but he did get a knock on the door from the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of the police. They handcuffed him and placed him under arrest, without explaining why. When Hejaaz’s relatives asked if the police had an arrest warrant, they were warned not to ask any questions.

The CID officials then rummaged through his office, casting through his legal files and seizing his phone and laptop. They asked him to dial numbers on his phone and asked if he recognised them. Before leaving with Hejaaz, they took two files from his drawers – both relating to District Court cases on properties owned by Yusuf Mohamed Ibrahim, a client.

Hejaaz’s family believes he is being targeted for his professional work as a lawyer and his peaceful activism for the human rights of Sri Lanka’s embattled Muslim minority.

Hejaaz is currently serving a detention order for 90 days authorized by the Sri Lankan President, even though a detention order can only be made by the Minister of Defence and Sri Lanka has no cabinet Minister for Defence. Under the notorious Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), one of the main tools used to perpetrate human rights violations in Sri Lanka, any “suspect” can be placed in detention – without charge and without being produced before a judge. The detention order can be renewed for a further 90 days and continue to be renewed for up to 18 months.

The PTA has long been criticized as an abusive law that has been used to crush dissent and forcibly disappear people, along with other violations. The Sri Lankan authorities have acknowledged the inherently abusive character of the PTA but have failed to repeal it as promised. The last government proposed its own legislation to replace the law but failed to amend the draft law in order to secure sufficient support for it before being replaced themselves.

Hejaaz, who has only been able to see his lawyer and family a few times and always in the presence of the authorities, could remain under arbitrary detention until October 2021. While in detention, he will have been subjected to arbitrary deprivation of his liberty and had a myriad of his rights violated, without being able to mount an appeal in the courts. The authorities have plunged him in this predicament on the basis of nothing more than his legitimate associations with Mohamed Ibrahim, the father of the bombers who perpetrated attacks on churches in Sri Lanka over Easter 2019. The authorities have publicly stated that the reason for his arrest were his interactions with the bombers and their family.

Mohamed Ibrahim’s sons, Inshaf and Ilham, were two of the seven bombers who set off six explosions across Sri Lanka on 21 April 2019, striking three churches and three five-star hotels on Easter Sunday and killing more than 250 people. The attacks were later claimed by the armed group calling itself ‘Islamic State’, but the connection with the group remains uncertain.

Hejaaz was connected to Mohamed Ibrahim in two ways. For the past five years, he had served as his lawyer, handling legal cases related to his business. Hejaaz and Mohamed Ibrahim were also part of the “Save the Pearls” organization, a charity that supports the education of underprivileged children, hoping to lure them away from criminal activities and drug abuse. Mohamed Ibrahim served as the organization’s treasurer as part of his wider philanthropic activities, a role he later handed over to his son Ilham, one of the bombers. Ilham was asked to step down from the role in 2016 by the organization’s board, barely a few months after taking over the post. Hejaaz, a member of the board, only attended eight of its 52 meetings in a span of 5 years.

This connection is being used to justify Hejaaz’s detention. The detention order says that Hejaaz is being investigated for allegedly “aiding and abetting” the Easter Sunday bombers and for engaging in activities deemed “detrimental to the religious harmony among communities”. No credible evidence has surfaced to establish any link between Hejaaz and the 21 April 2019 bombings. According to his family, all that the authorities are acting upon is a far-fetched suspicion.

Amnesty International is extremely concerned that the case and evidence against Hejaaz may now be subject to fabrication. A new allegation has emerged that a school supported by the Save the Pearls charity was responsible for preaching “extremism” and even providing the children “weapons training”. These charges lack credibility because nearly three months since his arbitrary arrest, authorities have so far been unable to substantiate their claims with evidence. Children who were interviewed by the police are now initiating legal action on the basis that they were interviewed without the presence of a parent or guardian. Through their parents and guardians, the children have filed Fundamental Rights applications with the Supreme Court seeking an interim order for the police to produce all arrest notes, video recordings and statements that the children were made to sign.

The Colombo Fort Magistrate has stated that CID officers tried to show the children pictures of Hejaaz before asking them to identify him as a hate preacher at their school. The identification parade has since been called off after objections were raised by Hejaaz’s lawyer, however this ordeal demonstrates a frank disregard for due process and the willingness of the authorities to attempt to frame Hejaaz.

Hejaaz has been subject to an unfair character assassination in local media by the authorities in an environment where anti-Muslim sentiment is rife, and prominent Muslim professionals have been unfairly targeted in the recent past. Hejaaz’s background is far from the picture that the authorities have tried to paint. Educated at a leading Anglican boys’ school in Sri Lanka, he is a lawyer at the Supreme Court and worked as a state counsel for the Attorney General’s department. He has a master’s degree in law from University College London, for which he won a Chevening scholarship. His legal expertise includes constitutional, contract, employment, human rights and property law. Beyond his legal work, Hejaaz has been involved in interfaith and reconciliation work, including through many high-profile cases, tackling the rising tide of Islamophobia that is now a key concern for human rights groups when it comes to Sri Lanka.

The Sri Lankan government must immediately restore Hejaaz’s due process rights, including producing him before a judge, allowing him to challenge the grounds of his detention, ensuring that he has unfettered access to his family and lawyers, and, in the absence of any charges of credible evidence of a crime being committed, release him. And to stop further such travesties of justice taking place, the Sri Lankan authorities should finally repeal the abusive PTA, and provide people who have suffered because of it the justice they are owed in the form of remedies and reparations.

Thyagi Ruwanpathirana

What is needed to keep Sri Lanka’s leopards roaming free?

What is needed to keep Sri Lanka’s leopards roaming free?

By Jagath Gunawardana

On Dec. 31, a fully grown male Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya) was found shot and killed at the famed Uda Walawe National Park. It was also reported that the forelegs of the majestic beast had been severed and its teeth pulled out, giving rise to a fresh public debate about the protection afforded to this charismatic species and whether the current conservation efforts are sufficient.

The Sri Lankan leopard is the largest of the four wild cat species found in Sri Lanka, and the apex mammalian predator on the island. It is also a charismatic large animal that is popular among locals as well as tourists. There are some who visit Sri Lanka mainly to view leopards. It is a favourite subject of wildlife enthusiasts and widely photographed.

The leopard has been protected under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance since 1964, the first wild cat to be given legal protection. The initial legal protection was partial, as it was still possible to kill a leopard by obtaining a permit to do so. This situation remained so until 1993, when an amendment to the law made the leopard a fully protected species, along with the jungle cat (Felis chaus), the other wild cat that was unprotected until that time.

The other two wild cat species in Sri Lanka, namely the fishing cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) and the rusty-spotted cat (P. rubiginosus), were given protected status in 1970. That means the fishing cat and the rusty-spotted cat had more protection under the law than the leopard from 1970 to 1993.

Legal protection

The last amendment to the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance in 2009 moved all four species into the newly established “strictly protected species” category. It is an offense to main, injure, harm or kill a leopard, or to keep a live animal, a dead body or any part of a body. It is also an offense to sell or expose to sell a dead body or any part or trade in live animals.

The offenses extend to the use of any implement, instrument or substance to commit any of these offenses. Furthermore, all these offenses are deemed to be cognizable offenses, that is, the offender can be arrested without a warrant. They are, in addition, deemed to be non-bailable offenses as well.

It is seen that there are quite strong legal provisions to protect the leopard in Sri Lanka. However, it is the enforcement of these provisions which is still the weakness. The Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) which is entrusted with the protection of all animals and plants and a large number of protected areas declared under the Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance, is severely understaffed.

It does not have enough staff to proactively give protection to species and habitats; the staff serve mainly to protect the habitats and also to take action against offenders. The Fauna and Flora Protection Ordinance has empowered the police too, but the police are entrusted with a myriad of law-and-order issues and also lack specialized training on animals and plants.

Another vital area that needs to be revamped is the capacity of the professional staff within the DWC, and this needs more officers and more training. This includes, but is not limited to, specialized subject areas such as the identification of animals and plants by genetic testing, detection and producing expert evidence before courts during prosecution, animal forensic studies, and coordinated operations with other state institutions.

The last amendment introduced a provision that allows any officer in the DWC of the rank of ranger or above, and who has more than 10 years of experience, to become an “expert witness” in a prosecution. There is a need to provide more training in specialized areas to make the best use of this provision too.

Need for proactive measures

The conservation and the protection of the leopard needs other proactive measures as well. Even though the leopard holds such an important segment in the tourism sector, given how popular wildlife tourism is, the authorities are yet to team up with wildlife authorities to have a comprehensive plan of action to protect leopards so that tourists will still be able to see them in the future.

Such an action plan needs to be multi-dimentional, tourism being one dimension. There are leopards in both the low-country wet and dry zones, and in the hill country up to the highest elevations, with a population in Horton Plains National Park itself. Hence it is needed to consider the populations of the leopards within and outside the protected areas and to have conservation and management actions to cover both these populations.

It is said that there are no more than 1,000 leopards remaining in the wilds of Sri Lanka. Furthermore, the subspecies found in Sri Lanka is an endemic one, found nowhere else on Earth.

But a number of leopards continue to be killed each year, both intentionally and accidently, taking a toll on the already low population. This animal is included in the National Red Data List as a threatened species within Sri Lanka.

It is very clear that time is fast running out for this charismatic carnivore and therefore urgent management action is needed to save this unique population for the future.

*Jagath Gunawardana is a Colombo-based environmental lawyer, lecturer and naturalist.

Faking “normalcy” and voting Corona to parliament

There are reasons for the more aware citizens to raise concerns over government’s recent shift in approach in controlling COVID-19. Perceptions that top bureaucrats responsible for the health sector are not independently so, also contribute to serious concerns. However much they brag about their independence in service, their work seem more aligned to the election agenda of the governing party. On July 03 when an individual in Jinthupitiya, Colombo 13 who was in self quarantine was identified as COVID-19 positive, DG Health Services Dr. Anil Jasinghe told media he would not be a “virus carrier” as he had completed the 14 day quarantine and was thereafter in self quarantine. But then, if Dr. Jasinghe was that certain the affected person would not be a “virus carrier” why was taxpayer money wasted on 154 persons to quarantine them for 14 days? This sounds no different to the Coast Conservation officials who said they expect sand from Ratmalana dumped to the sea from Mt.Lavinia would collect in Wellawatte.

Much different to them, the head of the taskforce responsible for prevention of COVID-19, army Commander Lt. General Shavendra Silva’s media briefing on 10 July on the new surge in COVID-19 positive numbers at Kandakadu and Senapura drug rehabilitation camps was quite objective. He clearly said, apart from the already identified 57, there were 196 affected cases reported in the morning, totalling 253. He had also told they were awaiting reports on 375 PCR tests already done and they may have positive cases, further increasing numbers. His assumption he had told media is that this outbreak could be from visits allowed for 116 of their relatives, or from those drug addicts the Courts decided to transfer, in the past few days.

He had also told media all precautionary steps have been taken to control any further spread. Yet he had warned, as there are expatriates also flown in, there can be reports of new cases tested positive and therefore community spreads cannot be totally ruled out. People should therefore take precautionary measures, he had warned.

That in fact is the reality. On the side of the people, COVID-19 has become a threat in the waning. Face masks are often forgotten in public. Social distancing seems no more relevant. Such social neglect does not come without change of priorities in government approach to COVID-19 prevention. The government removed most precautionary measures and restrictions imposed for COVID-19 prevention, in order to create social space for electioneering. Inter district travel that was in place, was removed. With very short notice, all island curfew was completely removed. Social distancing was gradually left aside and private buses came on the roads, reopening of schools in stages began, 500 students in a lot was allowed for private tuition, restaurants and hotels were allowed usual businesses and the situation at ground level seemed so much like that of the 2019 presidential elections.

With that, restrictions and conditions for election campaigning was only applicable to opposition campaigns and not for candidates of the government party. This open discrimination made COVID-19 control look irrelevant and the danger a bygone issue. These campaigns with media coverage make people feel the situation is “normal” once again creating a social psyche, COVID-19 is no more an issue in life.

Although election campaigns don’t have huge hoardings, massive public rallies, large and open public campaigns with huge money spent, there is public debate about who should be voted. With the election date nearing and an election mood slowly giving into collective engagements, social dialogue leaves COVID-19 unimportant and has lost attention in society.

In such context, increase in positive COVID-19 numbers have also lost notice in society. The 253 cases from Kandakadu and Senapura rehabilitation camps the Army Commander announced on 10 July morning reached an all time high of 300 in a day by evening. The Jinthupitiya case, Welikada remand prison case with another addition on 10 July and a Kandakadu rehabilitation camp Counsellor from Kottaramulla, Chilaw district tested positive with another Counsellor from Habaraduwa, Galle district tested positive too add to a growing possibility of community spread. Their number of contacts, the numbers subjected to PCR tests and possible positive numbers out of them are yet unknown. Meanwhile in Hambantota district, 15 from Ambalantota and 22 officers and prisoners from Angunakola prison and another 15 from Pelmadulla in Ratnapura district have been sent for quarantine. This gives an idea of the new spread that is creeping around.

There is no clear indication how Kandakadu and Senapura rehabilitation camps came to be COVID-19 clusters. If as the Army Commander suspects, it was with relatives who visited inmates, then not only the 116 visitors but their close contacts in hundreds would have to be traced. If the outbreak was due to drug addicts transferred to those camps on Court orders, again their close contacts can be very many. It could also be both sources that infected the camp inmates.

Tracing their contacts to the last and testing them for COVID-19 would mean PCR tests in thousands, not in hundreds. The extent of the possible spread cannot be otherwise traced, assessed and controlled. Till then we would be speaking about numbers in a social context that assumes everything is “normal” once again and is dominated by an election mentality. Maintaining and nurturing such social freedom till elections are over, may lead to a second wave. This second wave can be more severe than the first, with all indications of the spread now taking hold in the community.

But there is still the possibility of restricting it within controllable limits. That first needs re-imposing of an all island curfew from 09 in the night till 05 in the morning next day. Curfew will impose some restrictions in social life. But would not seriously effect election campaigns. Election campaign meetings, pocket meetings by candidates and collective election interventions should be totally banned. All schools should remain closed at least till elections are over. Private tuition classes should also be banned. Also, all detailed information about identified positive cases, their contacts and the number of PCR tests done should be made public. That allows others to avoid contact with suspected cases.

In summing up this whole essay let me say, COVID-19 prevention measures should be immediately slammed, and election campaigning should be allowed only within the space that would remain. Priority should be in electing a parliament with COVID-19 completely controlled and not one in a society threatened by a second wave that would be disastrous to everyone. Thus it is the responsibility of political parties and candidates in how they would design their election campaign within the space that COVID-19 prevention measures allow. If they cannot be innovative in meeting that challenge, they prove they are not competent in addressing the serious crisis the whole country is already in raising the question, “why elect them at all?

Kusal Perera

What Colombo-Beijing axis means to Sri Lanka

While the ongoing attempt by the US to renegotiate the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) has run into fierce opposition, the gift of a 2,300-tonne warship by Beijing to Colombo in early July this year has been warmly welcomed by Sri Lanka’s authorities. The commander of the Sri Lankan Navy, Vice Admiral Piyal De Silva, thanked China for the frigate and proclaimed it to be a sign of the good friendship between the two countries. According to China’s mission in Colombo, 110 Sri Lankan Navy personnel spent two months in Shanghai being trained how to operate the ship.

Later the same month, Reuters reported that Chinese President Xi Jinping offered Sri Lanka a fresh grant of 2 billion yuan ($295 million), a clear indication that Beijing is looking to further expand its influence over Colombo. Surprisingly, this has not caused any outcry, although it is well known that Beijing, through an adroit combination of grants, bribes and “debt trap diplomacy,” has successfully encroached on Sri Lanka’s sovereignty. Instead, Sri Lanka’s nationalists, (a eupemism that best describes Sinhala nationalists) consider themselves indebted to China for helping crush the 30-year old Tamil rebellion. It is a matter of fact that if not for the help of the Chinese, who, in addition to their military aid, gave the Sri Lankan government diplomatic cover at the UN Security Council, Colombo could not have won the long-running civil war.

As a consequence, Sri Lanka’s nationalists are grateful to China for its enormous help in bringing to an end what was widely regarded as an “unwinnable war,” and are unable to regard Chinese actions as inimical to Sri Lanka’s interests or impinge on Sri Lanka’s sovereignty. This, despite Sri Lanka having been forced to lease out Hambantota port in the south for a period of 99 years (to be managed and operated by Chinese state-owned China Merchants Ports Holdings) and China openly seeking to derail the Sri Lankan government’s agreement with Japan and India for the development of the Easter Container Terminal (ECT).

Instead, Sri Lanka’s nationalists are inclined to look upon Washington’s outright grant of $480 million over a five -year period in conjunction with the renegotiation of the SOFA agreement and negotiations for the Acquisition and Cross Servicing Agreement (ACSA) as the country becoming “one of the territories of the USA, if not its 51st State.” Unfortunately, such hysterical and outrageous hyperbole appear to be typical of Sri Lanka’s nationalists.

The explanation for this apparent irrational loyalty to China is attributable to the well-established premise that Sri Lanka’s Sinhala nationalists are a “majority with a minority complex.” As such they entertain the fear that the Tamils of Sri Lanka, with the support of the huge Tamil population across the Palk Straits in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, may prove to be a threat to their own independence or even cause the Tamil homeland in the northeast to be annexed by India.

Hence, the blind, unthinking loyalty to China by Sri Lankan nationalists in whose view China was not only the only country that had helped them beat Sri Lanka’s Tamils into submission, but also the country that has the military and diplomatic might to counter India should it prove to be a threat.

Sinhala nationalists, that is, the overwhelming majority within the Sinhala population, fear India because they believe that on the long term, New Delhi, either due to pressure from the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, which is angered by Sri Lanka’s ongoing mistreatment of their vanquished fellow Tamils, or to gain access to Sri Lanka’s port of Trincomalee, which New Delhi is known to covet, may directly intervene.

The Colombo-Beijing axis is primarily driven by Sri Lanka’s nationalists to counter their real or imagined threat from New Delhi. The opposition to Washington is a corollary, because Washington’s policy calls for a robust approach to break up the Colombo-Beijing axis and improve its own influence over Colombo.

Ana Pararajasingham

Ana Pararajasingham

Ana Pararajasingham is an independent researcher focusing on political developments in the South Asian region with particular emphasis on geopolitical developments impacting Sri Lanka and India. He was director of programs with the Switzerland-based Centre for Just Peace and Democracy between 2007 and 2009.

Sri Lanka: Weaponizing Archaeology?

By a Gazette notification, the Sri Lankan government appointed a Presidential Task Force for Archaeological Heritage Management in the Eastern Province on June 4, 2020. The Task Force has been tasked to identify sites with archaeological importance, identify and implement appropriate programs, identify land that should be allocated for cultural promotion, and preserve the cultural value of identified sites. Of significance is that the force has been established exclusively for the Eastern Province, where Tamil and Muslim communities share the space almost equally.

The appointment of an “all Sinhala” task force has already evoked a sense of fear among my Tamil friends. According to Tamil media, the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) has condemned the move as a step towards Sinhalesization and Buddisization of Sri Lanka. For me, it evoked memories of the end of the war. So, I wrote on my twitter feed, “In the war against LTTE, the government forces took control of the Eastern Province first. Then they focused the energy on the Northern Province, which led to the total military victory.” I guess I am also nervous. I decided to share an excerpt connected to the archeology department from my recent (2019) book, Post-war Dilemmas of Sri Lanka: Democracy and Reconciliation (published in London and New York by the Routledge, pp. 128-9).

The excerpt

‘What could be called the structural adjustment programs, where nationalist groups and institutions of the state collaborate informally, are aimed at limiting the presence and influence of Muslims in areas that are considered “sacred” by the Sinhala-Buddhists. One of the often-leveled arguments was that the Muslim structures including mosques, shops, and other religious symbols in the “sacred” territories are “illegal” (Wickramasinghe 2014, 400). The nationalists, at times, violently applied constant pressure on the state and the relevant institutions of the state to remove these illegal structures from the Buddhist sites. Consequently, many institutions, including ministers of the government, the Archaeology Department, the police, the Central Cultural Fund, and the Urban Development Authority (UDA), and so on, wittingly and/or unwittingly collaborated with nationalist groups to restrict the Muslim expansion and, in some cases, to remove their religious and commercial structures (Seoighe 2017). This pattern could be seen in places such as Dambulla, Balangoda, Anuradhapura, Deepavapi, and Devanagala.

On the premise that the Masjidul Khaira mosque in Dambulla was illegally built on a sacred Buddhist site, a roughly 200 men-strong mob demanded the removal of the structure and attacked it in 2012. In response, Prime Minister D.M. Jayaratne ordered the “relocation” of the mosque and the UDA asked that about 50 houses and 20 shops move out of the “sacred area.” Condemning the moves of the government, the Center for Policy Alternatives (2013) pointed out that the involvement of the UDA in this issue favoring the nationalist position “raises concerns that there is a concerted effort both by radical Sinhalese and the Government to evict Muslim families from the center of specific towns and cities” (59).

Why not Dinesh Gunewardena?

Sri Lanka won the cricket World Cup once, but never again. We started down the slippery slope almost the morning after we had reached the zenith of achievement. That was because we dismantled the winning combination which included Ana Punchihewa and Davnell Whatmore. The most crucial mistake we made was in the succession. The captaincy should have automatically devolved upon the vice-captain, who was one of the world’s best batsmen at the time; perhaps THE best. That was Aravinda de Silva. He was allowed to captain only sporadically.

The same mistake is being made by the Sri Lankan Opposition. In a situation in which the captain and commander-in chief of the national opposition, ex-President Mahinda Rajapaksa, cannot run for Presidential office, the obvious front runner in the choice of candidacy should be the vice-captain. There can be no question as to who the vice-captain is because the country’s citizenry sees it every night on TV news, whenever there is footage from the center of the nation’s political life, the parliament. And that man, that vice-captain, is Dinesh Gunawardena.

Now the obvious question arises as to why, though I had been mentioning Dinesh’s name for years, I had suggested Gotabhaya as candidate at one time—and why I no longer do so. I did not push early on for Dinesh though I kept dropping his name, because I remembered what another political family had done to a worthy successor who was outside the family. My father, Mervyn de Silva, was perceived as even closer to the SLFP’s Deputy Leader and the country’s Deputy Prime Minister Maithripala Senanayaka, than he was to Madam Sirimavo Bandaranaike. I therefore had a ringside seat watching the rise and fall of Maithripala, a left of center populist who had progressive views on foreign policy and was supported by the Left within the coalition. When Mrs. Bandaranaike’s civic rights had been removed and she was unable to contest the Presidential election of 1982, Maithripala, if given the SLFP candidacy, might have won. Instead he was overlooked, and double-crossed by his political ally Anura Bandaranaike. Hector Kobbekaduwa, a distant cousin of the Bandaranaikes, was chosen instead, but he too was backstabbed by the Bandaranaikes as was his ally and Mrs. Bandaranaike’s son-in-law Vijaya Kumaratunga himself.